Artist’s Statement

by Janet Biehl

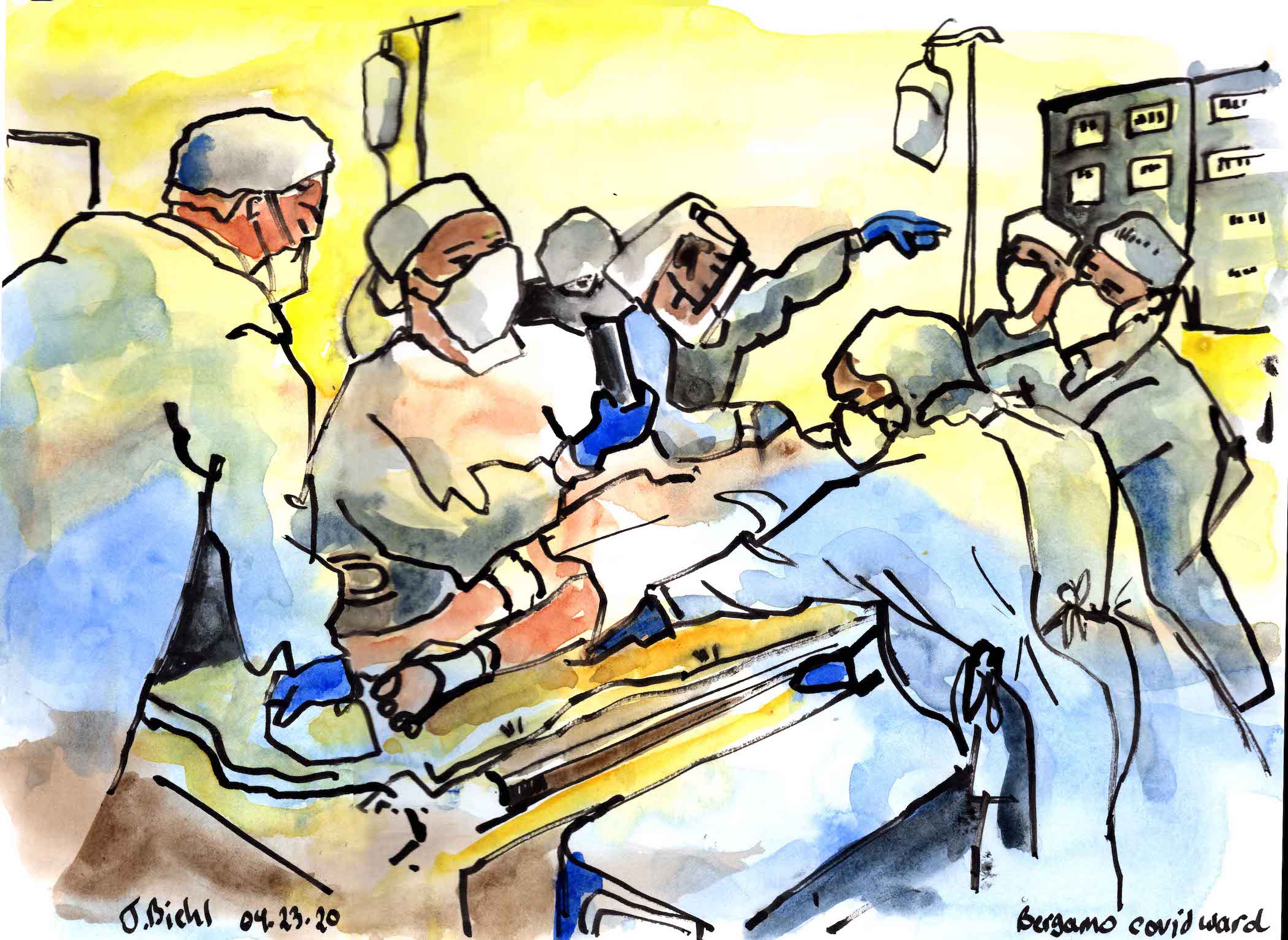

Images from the Homage to Medical Frontliners series by Janet Biehl

The older I get, the more art becomes for me an extension of my political and social engagement. In a world where the ruling powers are too often unjust, even malevolently so, I find that in my brief lifetime I can do a few things to help movements for long-term change: I can protest, I can vote, and I can draw.

I strive to practice an art of engagement, in which I witness and report on events, especially those taking place around me. I feel compelled to draw human activity, especially involving people in crowds, political demonstrations, in musical performances, especially events involving social justice.

Last year I was privileged to spend a month in northeastern Syria, where Kurds, Arabs, and Assyrians are collaborating to build a multiethnic democracy. Theirs is an astounding accomplishment, carried out while fighting a war against Islamic State and living with the ever present threat of invasion from Turkey. I was privileged to spend that month drawing the heroic people and groups I met there.

I realized that I want and need to draw subjects who stand up to the system or who are playing an active role in striving for the socially good. It is not always easy to combine art and politics without lapsing into propaganda. To avoid this pitfall, I try to get to the psychological core of people’s resistance, however seemingly hopeless, or their despair, however dark.

This storytelling kind of art has been called illustrative reportage, or visual journalism. To carry it out, I must first be attentive to the events, and to find their human core, I study my protagonists’ gestures and actions.

In March 2020, when the pandemic first gained its foothold in the United States, I stayed at home along with most of the rest of my fellow citizens. It meant I could not go outside to draw events, but then, in the deserted streets, there were no events. The action was in the COVID wards, where frontliners had the courage to work during a plague, to put their own health at risk for the rest of us, and in some cases to perish themselves. I wanted to draw them to pay homage to them.

I am not a healthcare worker, so I could not enter the wards. But a number of photojournalists were already doing so, and their fascinating and compelling work gave me the entry I needed. The work of visual journalists like Philip Montgomery whose series of photos in The New York Times Magazine in April allowed me to enter the wards vicariously.

Instead of a camera, I use india ink and watercolor on watercolor paper.

But first I prepare: I create a composition, often drawing from several photographs but sometimes just one, and develop a preliminary sketch. Sketching a complex scene helps me understand what is happening there, figuring out what is connected to what. I study the dynamic lines of the protagonists’ gestures and actions, how they interact with each other and with objects in their environment.

When I am ready to draw, I put aside the sketch, which has served its purpose of educating me, and I draw spontaneously, attacking the white paper with a bamboo pen and the blackest of India ink. The irregularity and sensitivity of the bamboo lets me draw with nuance, transmitting my emotions and insights directly onto the page. The experience of making split second decisions about where to move the nib next never fails to excite me. Overall, I let my subject guide my hand.

I hope the handmade imagery builds on the photographs, conveying a different kind of immediacy, a different sense of presence, suggesting the heroic core of the medical workers we all admire.

Our society should make sure that all these medical workers have PPE adequate to protect themselves, and it should compensate them adequately for carrying out their essential work. And until the virus threat is eliminated, we must all wear masks in public so that we too do not find ourselves in need of the services of these already overburdened heroes.

The works included in this issue were drawn and painted in March–April 2020, as the pandemic was paralyzing in New York City.

Janet Biehl is an author, translator, copyeditor, and artist living in Burlington, Vermont. She dreams of traveling the world with sketchbook in hand, reporting through visual storytelling on what she witnesses. She is currently spending her shut-in time during the pandemic writing and drawing a graphic novel about her April 2019 visit to Syrian Kurdistan. You can find Janet on Instagram: @jbiehlvt, Twitter: @jbiehlvt, and Facebook: @JanetBiehl.

Janet Biehl is an author, translator, copyeditor, and artist living in Burlington, Vermont. She dreams of traveling the world with sketchbook in hand, reporting through visual storytelling on what she witnesses. She is currently spending her shut-in time during the pandemic writing and drawing a graphic novel about her April 2019 visit to Syrian Kurdistan. You can find Janet on Instagram: @jbiehlvt, Twitter: @jbiehlvt, and Facebook: @JanetBiehl.